When a parent begins having bathroom accidents, it can be an emotional and worrisome time for everyone involved.

They may feel embarrassed or ashamed.

You may feel scared, frustrated, or unsure of what to do next.

What is important to remember is this:

Bathroom accidents among seniors are very often a health and mobility issue rather than a problem of laziness or lack of effort.

Understanding why this is happening is the first step towards keeping your parent safe, comfortable, and dignified.

Why do seniors have trouble reaching the bathroom in time?

Several age-related changes contribute to limiting seniors’ abilities to get to the bathroom in time.

Mobility and balance challenges

Many older adults move more slowly because of:

- Arthritis and joint pain

- Muscle weakness or frailty

- Balance problems

- Use of a cane, walker, or no device when they really need one

Even a normal urge to urinate or have a bowel movement may become urgent if it takes longer to stand up, walk, and sit down safely.

Bladder and bowel changes with aging

The bladder and bowel also change with age:

- The bladder may hold less urine.

- Muscles may be weaker, leading to strong urges and leaks.

- Prostate enlargement in men that hampers the flow and control of urination

- Constipation can press on the bladder and make accidents more frequent.

Medications and medical conditions

Certain medications and conditions can increase bathroom needs:

- Diuretics (“water pills”)

- Uncontrolled diabetes

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

Neurological conditions, including stroke and Parkinson’s disease

Often, all these factors together result in “not getting there in time.”

Key point: For most seniors, bathroom accidents are a medical and physical issue, not a personal failing.

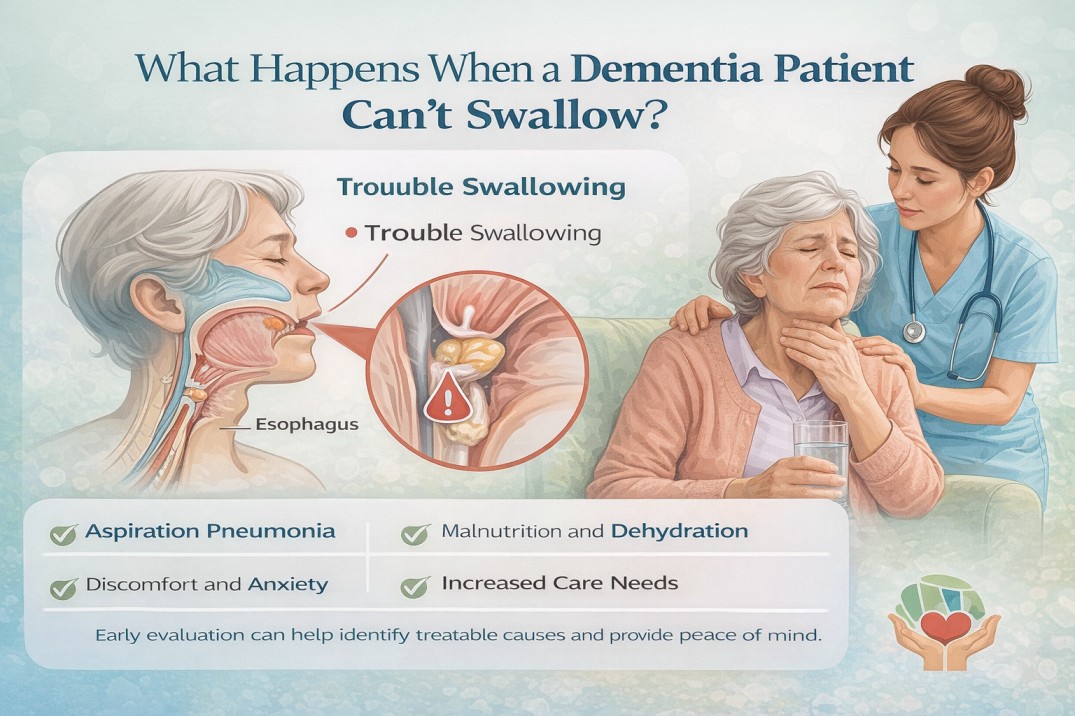

Can dementia or memory loss cause bathroom accidents?

Absolutely, dementia and memory issues can definitely be contributing factors to bathroom problems.

When Alzheimer’s disease or another dementing illness affects an individual, they may:

- Not recognizing in time, the urge to go to the bathroom

- Forget where the bathroom is, even within their own home

- The steps involved in toileting are forgotten: stand up → walk → pull down clothing → sit

- Confuse objects or locations, such as using a trash can or sink instead of the toilet

- Become distracted or confused and only realize they need the bathroom when it’s already too late

Issues such as these are the result of changes in the brain and are in no way because of stubbornness or lack of effort.

If you notice:

- New or worsening confusion

- Getting lost in familiar places

- Trouble following simple instructions

- Other memory or behavior changes

…it’s important to talk to your parent’s doctor about possible cognitive decline or dementia.

Key point: Dementia commonly impacts on toiletting because it alters memory, judgement, and the ability to sequence daily tasks.

Why are bathroom accidents more common for seniors at night?

Nighttime is particularly challenging for older adults, and for several reasons.

Getting up at night is more difficult and riskier.

Your parent might be at:

- Sleepy or groggy

- Stiff from lying down

- Unsteady on their feet

It may take much longer to achieve appropriate sitting, standing, and walking safely. That delay alone can cause accidents.

Poor lighting and disorientation

In the dark, it’s easy to:

- Trip over rugs, cords, or furniture

- Walk in the wrong direction

- Feel too afraid to get out of bed

This is particularly disorienting at night for seniors with memory loss, who may forget the location of the bathroom.

Increased nighttime bathroom needs

Some older adults naturally make more urine at night, which can be due to:

- Heart or kidney conditions

- Medications taken later in the day

- Swelling in the legs that “shifts” when they lie down

Key point: Nocturia brings together urgency, darkness, and unsteadiness; thus, increasing the chances of accidents and falls.

When are bathroom problems a sign of something more serious?

Bathroom accidents are common in older adults, but certain signs mean you should seek medical advice.

Call the doctor if you notice:

- A sudden change in continence (new accidents over days or weeks)

- Burning, pain, or discomfort when urinating

- Blood in the urine

- Fever, confusion, or sudden behavior changes (possible infection)

- Severe constipation or abdominal pain

- A major increase in falls or near-falls on the way to the bathroom

- New or worsening memory problems

A doctor can check for:

- Urinary tract infections

- Medication side effects

- Constipation

- Diabetes or other chronic conditions

- Neurological problems, including dementia

Some causes are treatable and may greatly improve your parent’s bathroom control.

Key point: Sudden or painful changes, or changes combined with confusion, should always be evaluated by a health professional.

How to talk to my parent about bathroom accidents without embarrassing them?

This is a sensitive topic, and your parent may already feel ashamed or defensive. A kind approach makes a big difference.

Try to:

“I’ve noticed it seems harder to get to the bathroom in time. How can I help?”

“This happens to a lot of people. Let’s see what we can do to make it easier.”

“Many older adults deal with this. It doesn’t mean you’ve done anything wrong.”

- Focus on safety and comfort

“I want you to feel safe and comfortable, especially at night. Let’s talk about some options.”

- Invite them into the solution

“Would you feel better if the path to the bathroom was clearer or better lit?”

“Would you like me to be there when we talk with the doctor?”

What practical changes can help my parent reach the bathroom in time?

Small changes at home can make a big difference.

Make the path to the bathroom safer and easier

- Clear clutter and move furniture out of the way.

- Remove loose rugs and electrical cords.

- Add nightlights or motion-sensor lights from the bedroom to the bathroom.

- Install grab bars near the toilet and in the shower.

- Consider a raised toilet seat or toilet frame to make sitting and standing easier.

Adjust daily routines

- Encourage regular bathroom trips every 2–3 hours during the day.

- Suggest a bathroom visit before naps, outings, and bedtime.

- Limit large amounts of fluid right before bedtime (without drastically restricting overall fluids unless advised by a doctor).

Choose easier-to-manage clothing

- Avoid tight belts, complicated buttons, or zippers.

- Use elastic waistbands or Velcro closures.

- Make sure your parent can easily pull clothing up and down without help.

Use protective products as backup

- Absorbent underwear or pads can provide extra security.

- Present them as a way to stay confident and active, not a sign of failure.

Consider bedside options at night

For seniors with significant mobility issues or high fall risk:

- A bedside commode can reduce the distance they need to walk.

- A urinal (for some men) can make nighttime toileting easier.

Key point: Think “safer, closer, simpler”—the easier bathroom access is, the fewer emergencies you’ll face.

What is incontinence in seniors and how is it different from just not making it in time?

“Incontinence” refers to the inability to control urine or bowel movements. This problem is different for everyone.

Common types include:

- Urge incontinence: The sudden, intense need to urinate, followed by leakage.

- Stress incontinence: leakage with coughing, laughing, lifting, or sneezing

- Overflow incontinence: Bladder doesn’t completely empty and causes frequent dribbling

- Functional incontinence: The bladder is working; however, the individual cannot reach the toilet in time due to mobility issues, confusion, or environmental barriers.

Many seniors have a mix of these types.

Key point: Not all bathroom accidents are purely “incontinence,” and not all are purely “can’t get there in time.” Often, it’s a combination, and a doctor can help untangle the causes.

How can professional caregivers support a senior with bathroom or incontinence issues?

Professional caregivers who are trained in senior care can play a huge role in maintaining safety and dignity.

A caregiver can:

- Provide scheduled reminders

- Gently cue your parent to use the bathroom regularly, preventing last-minute rushing.

- Assist with safe mobility

- Help your parent stand up, transfer, and walk to the bathroom while reducing fall risk.

- Help with clothing and hygiene

- Assist with pulling clothing up and down, wiping, and washing hands in a respectful, discreet way.

- Support seniors with dementia

- Guide them step-by-step through toileting.

- Use calm language and repetition.

- Offer reassurance when they feel confused or embarrassed.

- Protect dignity and privacy

- Experienced caregivers know how to respond calmly to accidents, clean up quickly, and preserve your parent’s self-respect.

At the same time, family caregivers get relief from constant nighttime wake-ups, heavy lifting, and the emotional strain of being “on call” all the time.

When should our family involve the doctor about bathroom problems?

It’s a good idea to involve the doctor early, rather than waiting until the situation feels unmanageable.

Before the visit, write down:

- How often do accidents happen

- Whether they involve urine, stool, or both

- Any pain, urgency, or changes in urine color or smell

- Recent falls or near-falls

- All current medications and supplements

Bring this list to the appointment. It helps the provider identify possible causes and recommend appropriate treatments or referrals.

If available, you can also ask the doctor whether a referral to a urologist, urogynecologist, gastroenterologist, or memory clinic would be helpful.

How can i take care of myself while helping my parent with bathroom issues?

Supporting a parent with bathroom problems can be exhausting—physically, mentally, and emotionally.

It’s common for family caregivers to:

- Lose sleep due to nighttime accidents

- Develop back or joint pain from lifting and helping

- Feel overwhelmed by laundry, cleaning, and constant vigilance

- Experience guilt, frustration, or burnout

To care for yourself:

- Ask for help from other family members or trusted friends when possible.

- Consider respite care or in-home help so you can rest.

- Join a caregiver support group, online or in person, to share experiences and coping strategies.

- Keep up with your own medical checkups, exercise, and social connections.

What should families remember about seniors who can’t get to the bathroom in time?

If your parent can’t get to the bathroom in time, it’s understandable to feel worried or overwhelmed.

Try to remember:

- This is usually a medical and functional issue, not a moral one.

- Many causes are treatable or manageable with the right support.

- Small changes in the home can greatly improve safety and comfort.

- Dementia and memory loss, if present, call for extra patience and guidance.

- You don’t have to do this alone—healthcare providers and professional caregivers can help.

If you’d like support with toileting, mobility, or dementia-related bathroom issues, A Place At Home – kirkland can help create a care plan that fits your parent’s needs and protects their dignity.

FAQs About Seniors and Bathroom or Incontinence Problems

Q1: Is incontinence a normal part of aging?

Some bladder changes are common with age, but frequent or severe incontinence is not something you just have to accept. It often has medical or functional causes that can be improved with treatment, exercises, medications, or environmental changes.

Q2: Can incontinence in seniors be improved or treated?

Yes. Depending on the cause, treatment might include pelvic floor exercises, bladder training, medication changes, treatment of infections, or surgery. A doctor or specialist can help determine the best options.

Q3: How can I reduce my parent’s fall risk on the way to the bathroom?

Clear the path, remove rugs, use nightlights, install grab bars, and consider a walker, bedside commode, or caregiver support—especially at night or after surgery.

Q4: When is it unsafe for my parent to be alone at night?

If they are falling, getting confused, wandering, or unable to manage toileting safely on their own, it may be unsafe to leave them alone. This is a good time to talk to the doctor and explore overnight home care options.

Q5: How can home care help with bathroom and toileting issues?

Home care can provide hands-on assistance with toileting, regular prompts to use the bathroom, mobility support, hygiene help, and respectful cleanup after accidents—all while giving family caregivers a much-needed break.

Helpful Resources for Families

For more educational information about aging, incontinence, and dementia, you may find these types of organizations helpful:

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always consult your healthcare provider about specific symptoms, concerns, or treatment options for your loved one.